I’m looking into the history of the illustrations of the Lady’s Slipper under the heading La Femme Fatale. I’ve started with Gerard’s Herbal (his own 1597 ed, but follow up with Johnson’s revision) and ended with Hilda Godferey’s pic of 1933: and everything in between. I’m looking for evidence that any of the illustrators ever drew a plant in situ; ie that the artist ever saw a wild, rather than a cut specimen sent to them/garden transplant. That is, how many artists could be said to have engaged with, and understood, the plant in its natural environment rather than merely as a botanical specimen.

In fact, historically – except for Yorkshire botanists who reported on Cypripedium in The Naturalist (in the 19th century)- it seems that very few writers, let alone artists ever saw the plant in the wild. (John Ray did see it.)

I have an extensive list of illustrators, and examples of their representations of “Our Lady’s Shoo.” Some are crude woodcuts, others watercolours of the greatest distinction. But I am struggling rather to find any representations in illuminated manuscripts: that is, I can’t find any earlier than Gerrard’s woodcut. If any one might have knowledge of a medieval representation (British or European) of the Slipper I’d really appreciate their letting me know!

Here are some examples.

- From Sowerby’s English Botany (1796)

- Gerard (1597)

- From Miller (1750)

- Hilda Godferey, with her own Lad’s shoos

- For interest – a roadside slipper in S.France

- Harriet Isabel Adams, 1907

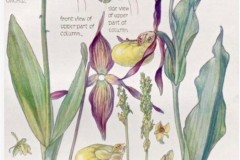

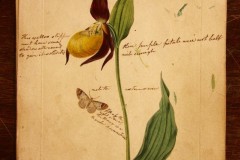

- John Curtis 1832

- Hilda Godferey 1932

From Plant to Painting to Page: John Curtis’ Lady’s Slipper.

John Curtis chose to illustrate the Lady’s Slipper, Cypripedium calceolus, on plate 416 of Volume 9 of British Entomology. (1832). It accompanied, for no reason, his delicate figure of the Blomer’s Rivulet, Melanippe bloomeri. The Cypripedium he used as his model was an authentic British specimen, though no longer “wild”. On the verso of his original drawing (below) in the archives of the Natural History Museum Curtis wrote “This was drawn from a Plant found wild at Castle Eden Dene Durham & transplanted into a Garden.” He gave more details in British Entomology: “This beautiful specimen was communicated by Mrs. Murchison, who informed me that the plant was found wild at Castle Eden Dene, and transplanted into a garden at Petersfield, Hants.”

Curtis was acquainted with the geologist Roderick Impey Murchison, (1792-1871). Murchison and his wife, Charlotte,

(1786-1869) settled in Barnard Castle, County Durham, early in their married life before moving to London in 1824. Their geological rambles would undoubtedly have taken them to the limestone fissures of Castle Eden Dene. The Cypripedium sent to Curtis by “Mrs Murchison” may have been collected by Charlotte during the time they lived at Barnard Castle. How did it find its way to Hampshire? The garden into which it was transplanted was that of her parents. Charlotte was born in Petersfield. Her mother, Charlotte Hugonin, was a keen gardener, described by her daughter as a talented florist and botanist. It’s quite possible that Mrs Hugonin visited her daughter in the North and collected her own Cypripedium specimen on a family excursion and took her prize home with her. That “This beautiful

specimen was communicated by Mrs Murchison” would suggest that Charlotte picked it from her parents’ garden when she visited them at the time it was flowering, in late May 1832. Curtis received it, drew it, had it engraved and coloured and published it on August 1st, 1832.

It’s unusual to find such precise provenance of a specimen. Though it is at one remove, Curtis’ illustration is taken from a genuine Castle Eden Dene Cypripedium, a locality where it has been long extinct. Of further interest is its journey from his original drawing to the print on the page. Its beauty owes much to Curtis’ colourer – who never, of course, saw the specimen.

The illustration (above left) is the “pattern plate”, an engraving coloured for Curtis’ inspection on which he has added comments. The plate as it appeared in the August, 1832 number is featured on the right. Curtis was very clear about how he wanted the colours. “These purple petals were not half rich enough….this yellow slipper must have some shadow all round to give it solidity.” The resulting hand-painted engraving was the result. It stands of one of the finest illustrations of the British Cypripedium – and we know exactly where it came from.

A.French May 1st 2020

The original drawing and pattern plate are reproduced by courtesy of the Natural History Museum, London, photographed by the author. Plate 416 is from James Charles Dale’s personal copy of Vol. 9 of British Entomology. (author’s collection).

Many thanks must go to Grace Touzel, metadata librarian at the Natural History Museum, London – not for the last time in this series of articles!

A Tale of Three Ladies: Hilda, Madge and Calceolus.

The frontispiece to Colonel M.J.Godfery’s sumptuous Monograph and Iconography of Native British Orchidaceae of 1933 is a reproduction of his wife’s beautiful painting of a Lady’s Slipper. Hilda Godfery was a botanical artist of great talent. Her speciality was orchids. In his preface Colonel Godferey tells us that “The coloured plates are life-size, from water colour drawings by my late wife. Of her 245 drawings of European orchids, 184 exhibited in London in 1925 were awarded the Royal Horticultural Society’s gold medal. and 229 were shown at the Fifth International Botanical Congress at Cambridge in 1930″

Hilda died in 1930, aged fifty-nine, three years before British Orchidaceae was published. Her hus-band – full name Masters John Godfrey – lost his soulmate. He dedicated the book to Hilda – “my wife, companion and enthusiastic fellow student of Orchids, by whom this book is illustrated, and without whom it would never have been written.” A fine photograph takes centre stage on the dedicaion leaf. Richard Mabey noted that it was the only book he had seen “where the dedication page is dominated by a photograph of the dedicatee, Godfery’s beloved late wife Hilda, posed amongst the foliage in her garden.” Hilda was, in fact, his second wife. She was nineteen when he married her in 1891. (He was 36). They spent much of their time abroad as well as in Britain, orchid-hunting, Hilda drawing specimens as they went along.

Her painting of the Lady’s Slipper is of a Swiss specimen. They found it in Bex, Switzerland, on May 15th 1913. It’s not at all likely that either of them ever saw an English one. Colonel Godfery saw the plant very much as a palearctic species and was quite happy to have seen it abroad. “Formerly in Durham, Yorks and Westmoreland. Now extinct or nearly so, though a few plants may linger on in places inaccessible to the public.”

A few plants had, indeed, lingered on, a closely guarded secret among a very few tight-lipped York-shire botanists. Articles and comment in The Naturalist from the 1880s onwards show the increasing alarm and despondency at the dwindling number of sites for the Lady’s Slipper, and the closing of ranks of those in the know. But then came an extraordinary article in The Strand Magazine in 1906. Hunting The Slipper – The Rarest British Wild Flower was written by the angling editor of the York-shire Post, William Carter Platts. He was a specialist first-class fly-fisherman from Huddersfield who wrote for several magazines and published books on the subject. He also produced “humorous” pieces which appeared in book form, one of which was The Whims of Erasmus. (1902). It contains a Sherlock Holmes pastiche involving his hero, Erasmus Tuttlebury. Perhaps this was how he came to be associated with The Strand. Although he clearly knew plenty about Holmes, who was the magazine’s bread and butter, there is no evidence that he knew anything of botany.

But he did know how to come up with a good story. He had been following up various leads for some years, and was able to give his readers a fascinating piece about the Lady’s Slipper. The hook for the article was the first ever photograph of a specimen in the wild, taken by Platts himself. The Naturalist of November, 1906 reproduced it.

The editor commented sniffily that “it professes to be the first photograph ever taken of the Ladies (sic) Slipper in its native haunts” and noted that “we have also received a photograph of a further specimen from Mr. J.F.Pickard.” But no mention whatsoever is made of another photograph in the article. Platts used it to accompany his story of how he was able to find his specimen.

In 1901 he was shown a secluded spot where the Lady’s Slipper had been discovered by the lady who found it, but “the slipper won easily” and she couldn’t find it again. Despite fishing being his passion – his favourite fish was the grayling – he made up his mind to hunt the slipper until he found it. He could learn nothing more until June, 1906,

when a little Wharfedale maiden, searching the woods for lilies, came upon a fine cluster, consisting of no less than eight stems. Fortunately, she was able to trace her steps to the spot. This stroke of luck gave me the opportunity to take the series of photographs illustrating this article, and including the first which have ever been secured of the plant blooming in its wild state. The exact spot is known to only three or four people, vowed to secrecy, and needless to say, the prize is being kept under observation, in the hope that its freakish nature may permit it to grace the same place another year.

Platts took a photograph of his “little Wharfedale maiden”. Her name was Madge Carradice, and she is the joint subject of a quite extraordinary photograph – possibly one of the most interesting examples of a botanical photograph ever taken. She is dressed in her Sunday best, wearing gloves and a beautiful hat, and proudly holds the rarest of British wild flowers. What must the botanists have thought when they saw the photo! Little Madge holding a plant that they had never seen, nor were ever likely to! Platts rubbed salt in the wound when he wrote

Here, through these hanging belts of mountain woodland, botanists hunt the elusive slipper year after year with undiminished zest, though their only reward be such pleasures of eternal hope as spurred on the ancient flower of chivalry in the quest of the Holy Grail…

He must have had contacts over a wide area, laid out money for information. Presumably Madge’s parents received something. Whoever took Platts to the spot – surely not Madge on her own – would have been rewarded. However it was, Madge Carradice did something that Hilda Godfery and generations of eminent botanists never managed to do – find their very own wild, British Lady’s Slipper. Here she is:

Selected References:

Godfery, Colonel M.J. Monograph and Iconography of Native British Orchidae. Cambridge, 1933

Mabey, R. Turning The Boat For Home: A Life Writing About Nature. Penguin, 2019

Platts, W. Carter. Hunting The Slipper. Strand Magazine. Volume 32. London, 1906

Various: The Naturalist, 1884-1922.

Photos by the author from his personal collection.

Sandals, Slippers, Sabots and Shoes. Which Lady Wears What?

A French website, (gerard.caubet.org) has this to say about the Lady’s Slipper:

Cypripedium calceolus est le nom savant du sabot de Venus. C’est tout simple ! Cypria est le nom chypriote de la déesse Venus, et pedium signifie sabot en latin. Quant à calceolus, sa signification est « petite chaussure ».En français on l’appelle le Cypripède. La religion peu enclin aux choses de l’amour a transformé sabot de Vénus en sabot de la Vierge ou pantoufle Notre-Dame. La légende veut que Vénus surprise à flâner dans la prairie par un berger s’enfuit, laissant derrière elle un de ses souliers devenus « le sabot de Vénus« .

Which, roughly translated, is: Cypripedium calceolus is the scientific name of the Sabot de Venus. Without any frills, then! Cypria is the Cypriot name of the Goddess Venus, and pedium signifies a sabot in Latin. Add on calceolus, signifying ‘little shoe’. In France it’s called the Cypripède. Religion, attracted to lovely things, changed Venus’ shoe to Virgin’s shoe, or Our Lady’s Slipper. The legend is that Venus, surprised walking in the fields by a shepherd ran off, leaving behind one of her slippers which grew into ‘the Sabot de Venus”.

If only it were that easy ! The origin of the name ‘Lady’s Slipper’ is a subject much broached by naturalists, horticulturalists and, it may be said, Uncle Tom Cobley and all. The simplest explanation given is the one above, though in Greek mythology the lost slipper belonged to Aphrodite – who became the Roman Venus. The most complicated is perhaps the one concerning the young Orchis, the libidinous offspring of a satyr and a nymph, who, when at a party thrown by Bacchus, made the mistake of seducing one of the god’s handmaidens. The result was that – depending which version you believe (or not) – he was chopped to pieces by the angry god or torn apart by wild beasts, perhaps from Bacchus’s own menagerie. Wherever parts of his body landed an orchid grew. Somehow his testicles landed in the sea, and Aphrodite rose from the waves. This is all to do with the orchid tubers, of course, and their resemblance to testicles. Gerard referred to them as ‘dogs stones’, which he lifted directly from Dioscorides, who wrote of Testiculo Canis with its floribus purpureis. He noted that the comely women of Thessalia put the powdered roots in their drinks, ad stimulandos coitus.

But Orchis’s grisly end can hardly have anything to do with the Lady’s Slipper. The orchids which sprang up after the party would surely have been Early Purples -the ‘long purples’ that Ophelia wore to indicate that sex was on her mind during her last hours. The women of Thassalia would have dug up macula -or any other species with with “dog’s stones” – for its tubers, and not wasted their time over calceolus because it doesn’t have tubers. It has a rhizome. But in general trying to untangle the web of classical references, cross cultural name changes and mistaken identities is a fruitless task, with only the priapic observations to relieve the tedium, like Dioscorides’ caution that orchid tubers definitely libidinem excitare.

Nevertheless, this sets a whole series of intricate questions for the enquiring mind. For the classicist, Sir Mortimer Wheeler’s exposition of the Aphrodite myth, which mentions nothing about the Orchis legend, can hardly be bettered in terms of scholarship and style; it can be found in The Scallop. Studies of a shell and its influence on humankind. (Shell, 1957). Put it together with an article by Grace Stoddard Niles, The Origin of Plant Names, published in The Plant World, an American journal, in 1902 and the enquiring mind will have all it needs; Niles explores the origins of the name Cypripedium, its naming by Linnaeus as Cypripedium calceolus and ponders the change in America from the Native American name ‘Moccassin Flower’ to the Lady’s Slipper, brought about by invading old-world botanists.

The association of the plant with footwear was clearly intercontinental, but why in Europe footwear became associated with Aphrodite/Venus is something of a puzzle. Despite the references to her slippers by those who quote Greek and Roman myths, in no depictions of the goddess in classical art is she shown wearing shoes. Indeed she wears nothing at all. Presumably if the Greeks really did associate the orchid with Aphrodite the thinking behind it was that if she did wear shoes – which she didn’t – they would be like the orchid’s labellum. The beauty of the flower might suggest that it should be associated with her. But then not everyone thinks it a beautiful flower: W. Carter Platts, writing in The Strand Magazine in 1906, couldn’t understand the fuss: ‘In itself’, he wrote, ‘and in spite of the gushful adulation of the average literary naturalist who has never seen it, the lady’s slipper is not entrancingly beautiful, and one’s first sight of it is apt to be a trifle disappointing. It is its rarity which is its chief charm, and it would be easy to name a score or two of common English wild flowers which outdo it for gorgeous colouring….the flower is not obtrusively reminiscent of the dainty feminine foot-gear of the present day, and one may be forgiven for speculating on the chances of its godfather having bestowed upon it the title of “my lady’s slipper’ in a moment of mental aberration when he could not think of ‘my lord’s boxing glove’ (which would,obviously, have been more appropriate) or his own particular lady suffering from an exceptionally severe attack of the gout the time of the christening.’

His bracing view, although certainly a mischievous sideswipe at the ‘average literary naturalist’, has something to be said for it. The ‘shoe’ of the Lady’s Slipper would not be something that Aphrodite/Venus would wear in Greek or Roman mythology, or during the Renaissance, where again she never wears shoes, but does generally sport a strategically placed towel. But the orchid is known in Italy as la scarpetta di Venere – which means Venus’ Slipper. The Italian name could go back a very long way, and the orchid may have known to the Romans as Venus’ Slipper. But scarpetta also means the morsel of bread, shoe-shaped, used for mopping up the pasta sauce left in the pan, so perhaps, in the Italian way, the goddess of love is also goddess of the kitchen, an idea promoted in our own times by publishers of Nigella Lawson’s cookery books. However that may be, scarpatta is far more appropriate to a goddess than the sabot. A sabot was, and is, a peasant’s clog. Undaunted by the unsuitability of the association, the French at some time began to call the orchid Sabot de Vénus, a curious form of footwear for the goddess of love but one which has stuck, and which is the common name for it in France. The comparison of the orchid’s libellum with a sabot is apt enough, as it looks a bit like one, but Venus’s Clog hardly has a ring to it; more of a thud. But it may be, given that Native Americans had their own folk-name for it, Moccasin Flower, that the French paysans of antiquity had their own simple shoe name for it and called it Le Sabot Fleur for the simple reason that it looked like a clog, or clog-like shoe.

By Elizabethan times it had become known in Latin as Calceolus Mariae, or in French Soulier de Notre Dame (calceolus, a small shoe, soulier, a slipper). At least, Lobel in his Plantarum Seu Stirpium Historia of 1576 knew it by then as Calceolus Mariae; but he also knew it as Sacerdotis Crepida (Priest’s Sandal), Papenschoen (Priest’s Shoe); Frauenschuh (Lady’s/Woman’s Shoe) and Drouwen schoen; the last probably referring to the clogs of that Dutch town, and bringing us back to sabots. He did not mention the Italian scarpatta, or the French sabot. The Spanish Zapata de la Dama, the Lady’s Shoe, or the Catalan Sabatta de Dame he is unlikely to have come across. We can see the etymological similarities between scarpatta, zapata, sabatta and sabot. Lobel’s mention of crepida, the nearest translation of which is sandal, might suggest slipper. He didn’t know the flower as a pantoufle, another word for slipper and another French name for it: Pantoufle de Notre Dame.

We can make a guess at when the shoe was given to Our Lady, the Virgin Mary, which is some time during the Medieval period.. If it was to be anybody’s shoe, slipper, sandal or clog the Catholic church would – as it did with many plants, as the writer on the French website points out – have it worn by the Virgin Mary, a dedication rather than a fashion statement; although, like Aphrodite/Venus, there was no tradition of Mary herself wearing shoes. Having examined hundreds of reproductions of illuminated manuscripts and many paintings which depict the Virgin Mary, as well as statuary gracing medieval cathedrals, I have found few which show her feet. They are almost always hidden by the draping of her skirt. When they are on view they are almost always bare, though there are a few exceptions in manuscripts when a shoe of some sort is shown as a little blob. As to the orchid, I have been able to find no trace of it in the margins of the many illuminated manuscripts I have pored over. It clearly itself had no religious symbolism, unlike many of the identifiable flowers which are commonly found in the margins. I can find no evidence that the Lady’s Slipper is ‘A variety of orchid associated with Mary in medieval art’, firmly stated by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona in ‘A Guide To Christian Art’. (2020) There is, however, one splendid example of a medieval Mary wearing shoes (which look like slippers) in what could hardly be a more spectacular setting.

‘Notre Dame de Belle-Verriere’ , generally ‘The ‘Blue Virgin’, (fig.1) fills the four central panels of a stained glass window in the south choir aisle of Chartres Cathedral. She is wearing brown leather ‘slippers’ which lace up the front. The glass dates from about 1150. The pilgrims who visited Chartres, themselves barefoot, will, whilst venerating the images, have taken in the details including the feet. Other images, high up in other windows, they would not have been able to see. There is one of a little later date which is a copy of the Blue Virgin, much smaller, in the south wall of nave in a series of panels depicting ‘The Miracles of Our Lady’, in which, again, Mary is wearing brown slippers/shoes. In the south transept, in glass of a similarly early date, below the rose window, she is at the top of the central lancet, again resembling the Blue Virgin but wearing green shoes. There may be others, but this should suffice to allow the supposition that in Chartres at least the Virgin wore ‘slippers’.

She is certainly not wearing sabots. She sports something similar to the footwear worn by the doctor (fig.2) . Shoes like this were for the wealthy. The glaziers of Chartres wanted their Lady in posh shoes. Shoes, then as now, were commodities and could define social status. The doctor’s footwear is as eye-catching as the flask containing a king’s water sample.He was proud of his lace-up shoes. But they appear to be a mis-matched pair. Yet, oddly enough, they resemble the Blue Virgin’s shoes; her right shoe, too, has an upper opening . Was this a fashion? If so, it may have been a male one.There is something masculine about the virgin’s shoe. Perhaps the glaziers didn’t want to suggest any worldliness about her, unlike the illuminator of Les Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Bery. The ladies of his acquaintance definitely wore what we might call slippers. (Fig 3). No common sabots here.

We can see, then, how an association between the Virgin and shoes may have come about. The picture in the mind of pilgrims as they made their way home was of a virgin who wore shoes, not the usual feet-hidden or barefoot Madonna. When the orchid became linked with her and her shoes may have something to do with the dissemination by pilgrims of a growing association of the virgin and footwear. But if Mary’s slippers and/or shoes can be traced back at least to the twelfth century, when she herself first became associated with the orchid is more difficult to establish. It can be stated with some certainty that its name across Europe and indeed the old and new world referred to it as a shoe of some sort from the time it was first given a name as the flower is just the shape into which a tiny foot would fit. The association with Mary must have come about during the mediaeval period, at the of the christianising of the names of plants by the church with which people (especially clerics themselves) were familiar, and dedicating a flower to the Virgin was an act of worship and veneration. It showed also an affection for the flowers themselves, not least because of Christ’s invitation to ‘consider the lilies of the field’. So looking for a plant which had features which might reasonably be ascribed to Mary would have been something of which God would approve,and as the glaziers of Chartres – and no doubt other cathedrals – had Mary wearing slippers then our orchid would have been a perfect choice, even if its flower was a sabot rather than a slipper.

As we have seen, Lobel hadn’t an English name for it because at that time it hadn’t been recognised as an English plant. Gerard referred to it in 1597 as ‘Our Lady’s Shoo or Slipper’, giving it an English name despite referring to the foreign specimen in his garden. But if the London herbalists didn’t know it as English, those folk who lived near those very few places where it grew in the remote parts of the northern counties must have done, and no doubt had long had a shoe name for it. At some point the name of Mary was added to whatever they called the plant. This could have been a spontaneous act of veneration during the medieval period begun by a member of the northern clergy following the fashion of ascribing her name to flowers, and spread over time through communities. But more likely is that the Mary ascription was brought by French monks who founded their monasteries in those isolated, and beautiful, parts of Yorkshire which they found ideal for leading their lives of prayer and seclusion.

Cistercian monks came to Yorkshire from Citaux, near Dijon, in Burgundy, in the first half of the twelfth century. In 1131 A group of them settled at a sequestered spot not far from Helmsley and founded Rievaulx Abbey. By 1143 there were some three hundred brethren there. One of the first things that needed to be done was to explore the area for plants. Knowing which ones were in the

local countryside was essential knowledge. The monks needed plants for food but especially for medicines; they needed them for their ‘virtues’. Hospitality and treatment of the sick was very much a part of monastic duty. The dispensary would be well stocked with plants and medicines prepared from them, not only for the monks, lay brothers and livestock but also for the sick who turned up at the gatehouse.

One of the plants they should have come across when searching the local slopes was the Lady’s Slipper. There are old records of Lady’s Slippers from the Helmsley area. It must have been there at the time the monks wandered the local valleys and it would be strange indeed if they never came across it; between their arrival and the Dissolution of the Monasteries they had four hundred years to find it. They should have found it in the first few years after they arrived, and recognised it as the Soulier or Sabot de Notre-Dame, or some such footwear, already named in France, possibly elsewhere, in honour of Mary. A few at least of those monks from Burgundy should surely have known the plant, the region being a stronghold to this day – if there is such a thing nowadays – of the Lady’s Slipper. The introduction of the name into England of a plant not officially known to exist in England until Thomasina Tunstall of Ingleton sent those Helks Wood specimens to Thomas Johnson in the 1630s may well have been before 1200 and by the monks of Rievaulx; for that matter, given that the Lady’s Slipper grew there, those of nearby Byland Abbey, or Fountains, or Furness Abbey in Cumbria. These were all Cistercian houses. Furness Abbey is not that many miles from places where Lady’s Slippers once grew and the same case could be made for Furness monks being responsible for introducing the French name, later Anglicised, to these shores. But in reality the plant could have been named independently by Cistercians at their different monasteries as they found it, as they knew what it was; there was no need for the name to have originated with one monastery. Whatever its English name before, or just after, the Conquest, the plant would have been recognised by the monks as one they knew, and the name gradually absorbed by the local villagers (those left after William’s torching of the villages during the Harrying of the North in 1069).

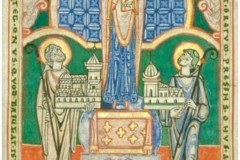

One of the founders of the Cistercian order was an English monk, Stephen Harding. In an illuminated manuscript of about 1125, in the municipal library in Dijon, is a leaf on which the said Stephen Harding is depicted presenting a little model of his church to the Virgin Mary.(fig.4) Look closely: she is wearing shoes similar to the ones in Chartres. The painter has taken great care with them. They are two-toned, light brown with a light orange stripe down the front possibly indicating the lacing joint. He wanted the shoes to be noticed; to say something. The whole is a beautifully balanced design, the colours still fresh – especially the green, much used at that time by illuminators in Northern France. To the Cistercians Mary wore shoes.

But did they ever refer to it as a Sabot de Notre Dame, putting clogs on the feet of the Virgin? Iconographic evidence shows that, when Mary did wear shoes, they were elegant and fashionable. Sabots belong to peasants. One of the misericords in Beverley Minster has a little carving in one of the stretchers which shows a man making them. (fig.5). He is carving them from wood. It dates from 1520, when a youngish Henry V111 was king. It’s a long time after the Cistercians settled in Yorkshire but the great monasteries were still functioning. The Beverley misericords came from woodcarvers in Ripon, close to Fountains.

When the sabot name was taken, possibly resurrected, in France, substituted for soulier and given to Venus to wear instead of Mary it’s not possible to know. It may have been during the Renaissance and the idea of reforming protestant clergy. It may not have been until the French Revolution that the name really took hold, hostility towards religion bringing about a shift away from the Virgin to Venus; but it can of course be argued that as they both express the idea of the Divine Mother they are essentially the same. But to the French it’s a Sabot de Venus, whilst we have stuck to Lady’s Slipper – though missing off the “Our’” in the protestant way. In Germany it’s still Frauenschuh, literally ‘woman’s shoe’ though it would rather be ‘lady’s shoe’, or ‘Gelb Frauenschuh’ , Yellow Lady’s Slipper, or Marien Frauenschuh, remembering the Virgin. A German folk name is ‘Woodpecker’s Nutsack,’ an appellation the origin of which is entirely outside the scope of the narrative. The French have retained Soulier de Notre Dame – Our Lady’s Slipper – as an alternative to Sabot de Venus but it seems that it’s the latter which seems more generally used. There are even holiday apartments and Hotels in the French Alps which have appropriated the name.

It was Linnaeus who firmly took the Lady’s Slipper back to classical times, having no truck with religious appellations. He took the old name calceolus, meaning shoe shaped, (the Latin for shoe is calceus) and cypripedium, from Kypris, a name for Aphrodite (or Venus) and pedium, from the Greek podi, meaning foot, or pedilon, ancient Greek for slipper/shoe. So it became, in a garbled way, Venus’s kind of footshoe slipper shaped thingummy, so we must be grateful for the common names which, whatever their origins, sum up the plant far more effectively. There appear to be no hotels anywhere in Europe named ‘The Cypripedium’, though ‘Hotel Aphrodite’ and ‘Hotel Venus’ are common in Greece and Italy.

Common in Georgian England was the straightforward association of Venus with sexuality, including prostitution. Covent Garden was known to local magistrates as The Square of Venus, populated as it was by street workers offering theatregoers a robust experience after the show. They were known as ‘the votaries of Venus’, or ‘daughters of Venus’. But ‘The shrine of Venus’ probably meant just the same to the ancients as it did to the rollicking Georgian dandies, invoking thoughts of Bacchanalian revels and sensual pleasures; of the kind which got Orchis into trouble in the first place. There is one representation, and the only one as far as I have been able to discover, which unequivocally portrays Venus with slippers. It’s Manet’s Olympia.(fig.6). She’s called Olympia, but is certainly Venus. She reclines on a couch, stark naked except for a bit of bling, an orchid behind her ear and a pair of slippers, one of which she dangles seductively from her toes.

But then, the Lady’s slipper has always been dangerously seductive.

AF June 2020

Photos:

Blue Virgin, Chartres and misericord, Beverley by the author.

Doctor: from Mirror in Parchment: the Luttrell Psalter and the Making of Medieval England. Michael Camille, 1998

Stephen Harding: from Images de la Foi: La Bible et Les Pères de L’Église d’ans Les Manuscrits de Clairvaux et du Mont Saint-Michel. Bibliothèque Municipale d’Avranches, 2002

Manet’s Olympia: from a postcard (€1.50), Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

This is a draft of a text of a work in progress which the author thinks might be of interest to Nats members (or perhaps not!) Endnotes and bibliography (etc) available upon request!